Issue #0

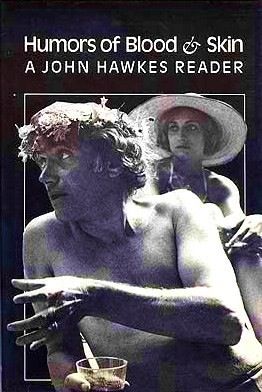

Humors Of Blood & Skin

A John Hawkes Reader

Plot

A Review of Humors of Blood & Skin: A John Hawkes Reader by Bruce Bawer

November 1984 - John Hawkes’s Fan Club

Humors of Blood and Skin: A John Hawkes Reader—the author’s thirteenth straight book from New Directions—contains just about what you'd expect: four short stories, excerpts from all nine novels, a fragment of a novel-in-progress, brief autobiographical prefaces to each of the selections. A fair enough overview. But the book’s primary purpose, one senses, is not so much to provide the reading public with snippets from twenty-year-old novels as it is simply to exist, and by existing to get us all a little bit more used to the idea that John Hawkes is an important writer, a modern classic, an Author for the Ages. Indeed, William Gass’s introduction stops just short of proclaiming Hawkes’s divinity—and the man even signs himself “William H. Gass, Washington University, St. Louis,” as if this were a scholarly document of sorts, which in a way it is; for though Hawkes has achieved literary eminence in the great world beyond the campus gates, the hotbed of Hawkesianism is, was, and ever shall be the English department.

In fact, the Hawkes phenomenon was born in the English department—in English J, to be specific, a creative writing course taught by Professor Albert J. Guerard at Harvard in the autumn of 1947. Hawkes, an undergraduate, was a student in English J who had somehow discovered—quite on his own, apparently—that plot, character, setting, and theme got in the way of “totality of vision” and were therefore “the true enemies of the novel.” Guerard was so impressed by the stories that young Mr. Hawkes had written under the influence of this hypothesis that he took the precocious theorist and his work straight to the offices of New Directions, whose president, James Laughlin, was a Harvard alumnus and Guerard’s friend. Laughlin was impressed too, so impressed that by the time Hawkes had his A.B. in hand, Laughlin had not only published Hawkes’s novella, “Charivari,” in New Directions 11, but had issued his first novel, The Cannibal, with an introduction by Professor Guerard.

And what an introduction it was! Single-handedly, it set the schizophrenic tone— half scholar’s, half booster’s—that one academic after another, upon climbing onto the Hawkes bandwagon, has since taken as his own. Without bothering to identify himself as Hawkes’s teacher, mentor, and sponsor, Guerard lets fly the accolades; he situates Hawkes on a level with Kafka, Faulkner, and Djuna Barnes (doing so “advisedly,” he claims, in a wonderful imitation of scholarly circumspection, because “I think the talent, intention, present accomplishment and ultimate promise of John Hawkes are suggested by some conjunction of these three disparate names”), and with a number of other imposing figures. Yet the terms in which Guerard executes this comparison are peculiar indeed. To him, the magnificence of his protégé’s talent is demonstrated by the fact that Hawkes “is now, at the outset of his career and at the age of twenty-three, a rather more ‘difficult’ writer than Kafka or Faulkner, and fully as difficult a writer as Djuna Barnes”; that “as a picture of the real rather than the actual Germany, and of the American occupant of that Germany, The Cannibal is as frankly distorted as Kafka’s picture of the United States in Amerika”, that The Cannibal is characterized “by a very distinct reluctance (the reluctance of a Conrad or a Faulkner) to tell a story directly”; that, in The Cannibal, a degree of “difficulty and distraction is provided, as in Djuna Barnes, by the energy, tension, and brilliance of phrasing often expended on the relatively unimportant”; that The Cannibal’s “total reading of life and vision of desolation [are] as terrible as that of Melville’s Encantadas”; that “as Kafka achieved a truth about his society through perhaps unintentional claustrophobic images and impressions, so Hawkes . .. has achieved some truth about his.” In short: The Cannibal is as difficult, as distorted, and as depressing as the work of many great writers. Therefore The Cannibal is a great book and Hawkes is a great writer.

If such characteristics automatically made a book great, then The Cannibal would be a work of the utmost distinction. The novel is nominally set in an imaginary German town, Spitzen-on-the-Dein, in 1914 and 1945, but things are so surrealistically confusing that the novel cannot really be said to have anything so pedestrian as a setting. Similarly, Hawkes gives us several names, but nothing resembling a human being ever takes form around any of them, so he’s safe there, too: no real characters here. He’s not out to evoke a particular place, time, or person but “to render [as he confides in Humors of Blood and Skin] my own vision of total destruction, total nightmare.” Perhaps the best way to understand what Hawkes means by “vision” is to describe The Cannibal, or at least its first few pages, in some detail.

The book begins with the release of inmates from a mental institution near Hawkes’s mythical town. One of the inmates, a pseudo-character named Balamir, makes his way into the town, and Hawkes provides an inventory of the things he passes along the way: the “fallen electric poles,” the “piles of debris,” the “same tatters of wash hung for weeks in the same cold air.” By the end of the first page, we’ve gotten the point: this place (though we can hardly recognize it as a place) has suffered total destruction. But Hawkes is just getting started. He doesn’t want merely to establish that everything in sight is broken to bits, failing apart, or rotting away, and then move on to something else. Heavens, no. He wants to create a vision. And since this is not Vladimir Nabokov or Nathanael West (or, for that matter, Edmund White, James Purdy, or Truman Capote), what that means is that we get more of the same—and more, and more, and more:

——Piles of fallen bricks and mortar were pushed into the gutters like mounds of snow, smashed walls disappeared into the darkness, and stretching along the empty streets were rows of empty vendors' carts .... Bookstores and chemist’s shops were smashed and pages from open books beat back and forth in the wind, while from split sides of decorated paper boxes a soft cheap powder was blown along the streets like fine snow. Papier-mâché candies were trampled underfoot….——

Evocative, yes. But it’s also quite enough. Not for Hawkes. He drops Balamir for the moment, tosses a few more disembodied names at us—Madame Snow, her daughter Jutta, the Mayor, the Signalman, the Census Taker—only to return, immediately after introducing each of them, to his catalogue of the smashed, the moldy, the trampled, the fallen. Hawkes informs us that the legs and head were lopped off the town’s statue of a horse, that the “rattling trains” were halted by “the curling rails,” that “the empty shops and larders” were filled “with a pungent smell of mold,” that the only horse left in town was “one gray beast” who “trampled, unshod, in the bare garden, growing thinner each day, arid more wild,” that “banners were in the mud, no scrolls of figured words flowed from the linotype, and the voice of the town at night sounded weakly only from Herr Stintz’s tuba,” that “there was nothing to eat. .. and tables were piled on one another, chipped with bullet-holes,” that the town was full of “piles of cold rubbish and earth.” Et cetera, ad infinitum.

This is what Hawkes means by vision. This crumbling town is supposed to rise up and haunt one, the way Stonehenge does at the end of Tess of the D’Urbervilles. But it doesn’t work. Why? One reason, at least, is that there are people in Tess, people we believe in and care about, who give those weathered stones symbolic meaning, who make them matter. The same holds for James’s golden bowl, for Woolf’s lighthouse, for Fitzgerald’s green light at the end of Gatsby. Reading The Cannibal, one wants desperately to be moved, but one isn’t; in spite of Hawkes’s prepossessing litany of broken buildings and smashed statues, the lack of human dimension makes the whole thing surprisingly inert.

Nonetheless, The Cannibal achieved what it was meant to. It was no bestseller, but, largely thanks to the attention Guerard attracted with his prefatory puffery, it was a succès d’estime. And Hawkes’s subsequent novels—eight of them published between 1951 and 1982—solidified his position as a leading visionary novelist. Of course, none of this succès came about without help. As Hawkes’s body of work took shape, so did an equally noteworthy body: the John Hawkes “fan club,” a well-defined group of academic critics who have gathered around Hawkes and his works in the manner of a corps of disciples, and who have been instrumental in the rise of Hawkes’s fortunes. Among them are Leslie A. Fiedler; Robert A Scholes (Hawkes’s colleague at Brown University), who included a chapter on Hawkes in his influential 1967 study The Tabulators; Donald J. Greiner, Frederick Busch, and John Kuehl, authors of critical studies of Hawkes’s work published in the mid-Seventies; John Graham, editor of a collection of essays on Hawkes’s novel Second Skin; and of course, Guerard, who has published a number of articles on Hawkes. The fan club convenes irregularly, at university symposia and MLA conventions, to discuss Hawkes’s work. Its chief document is an outre volume entitled A John Hawkes Symposium: Design and Debris (1977), which contains the proceedings of a conference at Muhlenberg College whose speakers included not only most of the gentlemen listed above, but—just to establish beyond a doubt that the real purpose of this conclave was not criticism but celebration—Hawkes himself. To keep things entirely in the family, A John Hawkes Symposium was published by (ahem) James Laughlin.

The locust-like descent of scholars upon a contemporary novelist is, of course, hardly remarkable; many a writer has had the dubious honor of being paraphrased to death in dissertations and misinterpreted from the lecterns of hotel conference rooms. But few, if any, have seemed to pay so much attention to their academic expositors, or have owed them so much, as has John Hawkes. And few have been the subject of such unqualified veneration. For as far as the club members are concerned, Hawkes is the litmus test for the modern critic. “It’s interesting, you know,” Guerard says in his keynote address at the Muhlenberg gala, “that some of the alleged ‘modernists’ [during Hawkes’s Harvard days] really didn’t like Jack’s work. . . .” The operative word is alleged: these self-styled modernists, simply by failing to admire the work of their colleague’s undergraduate protege, proved themselves to be Victorian fuddy-duddies. “The fact is,” Guerard complains elsewhere, “that older and professional readers, with a few honorable exceptions, did not like Hawkes’s work at all. They incorrigibly looked to those elements of fiction Hawkes saw as his ‘enemies’ at the beginning of his career.” Well, you know these dishonorable, incorrigible critical types: they just go around looking for trouble.

Not like the members of the Hawkes fan club. The Hawkesians, at least on the subject of Hawkes, agree on just about everything. It is hard to read through their criticism without inferring that they have all subscribed to some party platform. They all, for example, enjoy complaining that Hawkes is ignored outside the academy. “There has been marked discrepancy,” writes Kuehl, “between the academic and the general reception of John Hawkes’s novels. Eminent literary critics such as Albert J. Guerard, Leslie A. Fiedler, Robert A. Scholes, and Tony Tanner have praised his art, yet Hawkes commands only a small following, many of whom are college teachers and students.” Greiner echoes this sentiment, referring continually to Hawkes’s “obscure reputation,” his “lack of readers,” his being “unknown and unread.” He calls this obscurity “deplorable” and “a cause for concern.” “I do hope that what I have to say will encourage more serious readers to pick up his novels,” declares Greiner. “A writer of Hawkes’s genius deserves a wider hearing.”

One would hardly know that these men are carrying on about someone who, as a result of the efforts of their cabal, has long since escaped obscurity—who has been front-paged in The New York Times Book Review and the other major literary periodicals for over two decades; whose books clog the shelves of literary bookstores; who has been sanctified by the Ford, Rockefeller, and Guggenheim gods; and who is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. To be sure, this Hawkes-is-neglected routine started decades ago, when it was somewhat less of an untruth. Fiedler, for example, wrote in his introduction to The Lime Twig (1961) that Hawkes was “perhaps . . . the least read novelist of substantial merit in the United States,” and described an ad in which Laughlin denounced the editors of Partisan Review for not printing “the work of such writers as Edward Dahlberg, Kenneth Patchen, Henry Miller, John Hawkes, and Kenneth Rexroth.” Fiedler noted: “God knows that of all that list only John Hawkes really needs the help of the Partisan Review.” Well, in the past two decades—thanks to the puffery of partisans like Fiedler—Hawkes has eclipsed all those writers, except Miller, in celebrity. But the Hawkes-is-neglected theme plays on. A typical complaint of a Hawkes clubman today is not that Hawkes can’t get into the Partisan but that he does not have the readership of his fellow “black humorist,” Joseph Heller—whose books are, of course, huge bestsellers. How famous, one wonders, can you become and still be considered obscure?

The clubmen also like to delude themselves (and mislead everybody else) with the notion that if Hawkes is less well known than he should be, it’s because only academics have what it takes to appreciate him. Kuehl puts it this way: “Popular reviewers and their audiences [i.e., everybody off-campus], failing to comprehend how his work operates, also fail to understand what it expresses.” This is merely a variation on the familiar academic conceit that everyone outside of academia is (to be kind about it) out of touch. It pleases the club to spread this sort of self-flattering fertilizer, and to feel that the novels of Hawkes are an all-in-the-family thing—of-the-academy, by-the-academy, for-the-academy. This possessiveness surfaces almost embarrassingly in Fiedler’s introduction to The Lime Twig:

——Who . . . reads John Hawkes? Only a few of us, I fear, tempted to pride by our fewness, and ready in that pride to believe that the recalcitrant rest of the world doesn’t deserve Hawkes, that we would do well to keep his pleasures our little secret. To tout him too widely would be the equivalent of an article in Holiday, a note in the travel section of the Sunday Times, might turn a private delight into an attraction for everybody. Hordes of the idly curious might descend on him and us, gaping, pointing—and bringing with them the Coca-Cola sign, the hot-dog stand. They've got Ischia now and Mallorca and Walden Pond. Let them leave us Hawkes!——

So why is this Ischia among novelists appreciated only in the academy? Because he’s difficult, of course. Guerard’s characterization of Hawkes as “a rather more ‘difficult’ writer than Kafka or Faulkner” is echoed by Kuehl (“his manipulation of complicated techniques and attitudes makes him one of the most difficult American novelists since Faulkner”) and by Greiner (“Hawkes is as important a writer as Updike and Nabokov. As difficult as they sometimes are, he is difficult constantly”).

Hawkes is great because he’s difficult. And he’s difficult because of that unconventional vision. Writes Kuehl: “Those who expect formal and conceptual materials associated with traditional realism are perplexed, for Hawkes mocks these as anachronistic. Substituting ‘vision’ for ‘novel’ and ‘reality’ for ‘realism,’ he would support Robbe-Grillet’s contention that verisimilitude is no longer the issue. Old familiar fictional elements . . . seem banal to an anti-realist who rightly considers himself unique.” This is the key to the fan club’s defense of Hawkes. Whatever shortcomings non-club critics may fault him with, the club’s answer is simple: Hawkes doesn’t write by the old rules, so you can’t judge him by old rules. Characters that never come to life? Instead of characters, Hawkes gives us voices. Greiner declares of two characters in The Beetle Leg that neither “is meant to be fully developed. It is their voices that count.” No plot? Instead of plot he gives us vision. “The difference,” explains Greiner, “is between the conventional novel with its structure based on meaning and the experimental fiction with its coherence based on imaginative vision.” “There is no room for characters,” asserts Frederick Karl about The Beetle Leg, “as there is no room for narrative or plot. The ten episodes ... are connected only by landscape and language. Just as the former is a state of mind more than a place, so the latter exists more in Hawkes’s imagination than in the ordinary resources of language.” What, one must wonder, makes voices without characters better than characters without voices? Why is an “experimental fiction” based on “vision” without “meaning” preferable to a conventional novel that has both?

The fan club divides Hawkes’s oeuvre—and quite rightly, too—into two distinct visionary epochs. Some of the boys call the first one the “waste land” period. Besides The Cannibal, it includes three novels: The Beetle Leg (1951), The Lime Twig (1961), and Second Skin (1963). The books read almost like rewrites of one another: the “visions” are virtually identical; only the pseudo-characters and pseudo-settings are different. The Beetle Leg has, in place of a German village and asylum, a town and dam in the American West. A man named Mulge Lampson is buried in the dam; ten years after his death, we peek in on the surrealistic lives of his shadowy survivors. Hawkes tries to build the dam up into a major symbol, but, as with The Cannibal, the lack of human dimension defeats him. The Lime Twig, though pretty much a rerun, is a step in the right direction. In a gray, grim pseudo-London, a fat, pathetic, lonely pseudo-man named Hencher and his landlord Michael Banks join in a scheme to kidnap a racehorse named Rock Castle. Early in the novel, Hencher gets kicked to death by the horse, and later on Banks and his wife Margaret meet equally unpleasant ends; one cannot help but feel that Hawkes kills off Hencher so early because he perceives that Hencher is turning into (horrors!) a real human being for whom the reader might actually develop (God help us!) sympathy.

The last “waste land” novel is Second Skin. The narrator is Skipper, whose present is the Edenic bliss of a tropic island, and whose past is a parade of suicides—his father’s, his wife’s, his daughter’s—and the murder of his son-in-law Fernandez. There are some genuinely affecting passages in Second Skin, and they are affecting because Skipper is at least the beginning of a real character, and the settings and situations through which he moves are the beginnings of real settings and situations. Indeed, the movement throughout these four “waste land” novels is quite distinctly away from the ineffectual “visionary” method of The Cannibal and toward a more nearly effective, and conventional, approach. Thus, though none of these four early novels works as a whole, the last two, at least, hold promise.

In the novels that follow Second Skin, unfortunately, Hawkes goes off in a new direction, chasing a new “vision.” This might be called his pornographic period, for if these books were more disciplined in style and structure, they would make fine additions to any adult bookstore. Guerard called the first three Hawkes’s “trilogy of sex,” but with The Passion Artist (1979) the trilogy became a tetralogy, and then in 1982 a fifth came along in the form of Virginie: Her Two Lives, and it was suddenly embarrassingly clear that this wasn’t a nice, naughtily adventurous little cluster of Updikean or Rothean sex novels but a whole new career founded on prurience. Gone is the desperate attempt to avoid characters, settings, plots; not that Hawkes suddenly develops a great talent for these things—he simply doesn’t struggle against them. Since the “vision” of these later books is almost exclusively carnal—focusing, for the most part, on very clearly defined types of sexual interaction between people with very clearly defined relationships—it is all but impossible for Hawkes to stay as far away from the conventional novel as he would like.

Still, he does his best. He manages to set The Blood Oranges (1971) in some unnamed tropical demi-paradise that never does come into focus. The book is about two men who swap wives: Cyril, the “sexually liberated” narrator (whose puerile philosophical mots—e.g., “the only enemy of mature marriage is monogamy”—Hawkes seems to take completely seriously), initiates the swap; the other man, Hugh, a pornographic photographer, eventually comes down with terminal guilt pangs and commits suicide, after which his wife Catherine is institutionalized and Cyril’s wife Fiona leaves, taking with her Hugh’s three children. Death, Sleep and the Traveler (1974) is about one Allert, a collector of pornographic albums who has been sharing his wife Ursula with his friend Peter, a psychiatrist; Allert takes a cruise, on which he has an affair with one Ariane. She disappears at sea; Allert is accused of murder; Ursula testifies in his behalf, then clears out. Travesty (1976) is a récit; the unnamed narrator is driving a car across France; in the backseat are his daughter Chantal and Henri, a poet who has been sleeping with both her and the narrator’s wife Honorine. At the beginning of the book the narrator tells his passengers that he’s going to smash the car into a wall a few miles up the road and kill them all; the remainder of the book consists of his recital, along the way, of anecdotes about sex with his mistress and his delight in pornography. The Passion Artist is about a man named Konrad Vost whose surrealistic sexual adventures involve his daughter, a prostitute, and his mother, a prison inmate. Virginie: Her Two Lives is about an eleven-year-old French girl who lives in two centuries. In 194.5 she lives in a “Sex Arcade” with her brother, a raunchy cab driver named Bocage; in 1740, she lives with a “sensualist” named Seigneur, whose kept women burn him to death at the end of the book.

The attitude toward sex in these novels is sub-adolescent, and the eagerness (and utter inability) of the author to appear hip is pathetic. Hawkes wants desperately to come across as a roue, but he only succeeds in sounding like a middle-aged English professor who wants desperately to come across as a roue. Even a giggly twelve-year-old would soon tire of Hawkes’s unrelieved preoccupation with clothing, underwear, and naked bodies—a fetishistic obsession which causes some sections of Death, Sleep and the Traveler, for example, to sound like fragments from letters to Penthouse:

——Ursula made no attempt to defend herself against the handfuls of heavy lotion which Peter, as I could now clearly see, was smearing across the tight rounded surfaces of Ursula’s translucent underpants.

I was sexually aroused in the depths of my damp swimming trunks as I had not been since long before the disappearance of the ship’s home port….

“Let me hear what you can do with your flute.”

“Very well,” she answered then. “But it may not be as easy as you think. You see, I play in the nude.”— —

Parts of Virginie, meantime, read like excerpts from a poor translation of an X-rated French movie:

— —“Do you think I could ever wear such foolishness? Sylvie,” she cried, “Sylvie does not wear the frilly underpants!”

“Look there,” whispered Sylvie. “See how gently Monsieur Pidou uses the soap!”

“And little Déodat,” whispered Yvonne, “how buttery he is, and how red!”

“Oh, the endless buttons of sailor pants!”— —

This sort of nonsense, however, is innocuous compared with the sadomasochism that pervades the later novels. In Travesty, for instance, the narrator boasts about spanking his mistress Monique, and of her coming after him immediately thereafter with a whip: “I thought she meant only to whip me lightly to ejaculation, a process, which, at that moment, I imagined as a fulsome and brilliant novelty.” But she flays him bloody, and does so “with joy” and “with superb contempt.” And as a result: “In my defeat and discomfort I too felt a certain relief, a certain happines for Monique . . ..” Cyril, the philosopher of The Blood Oranges, asserts that “most of us enjoy the occasional sound of pain, though it approaches agony.” And the grubby gamboling of Virginie inspires such lines of dialogue as the following:

——“Virginie!” she called in a breath of pure amusement, “fetch the kettle. We are going to introduce Lulu to the raptures of steam!”

“Mesdames!” Seigneur cried happily, and to me surprisingly, as he came at last among us and took his place at my table. “Mesdames, she who loves well punishes well!”——

I will not dwell on Hawkes’s obsession with little girls, or with bestiality; but reference must be made to the scene in Virginie that begins with Seigneur delivering the following speech to one of his kept women, Colère:

——“No creature is too deformed to love,” he said. “No act is too unfamiliar, too indelicate to perform. Repugnance has no place in the heart of a woman such as you. By embracing an animal, or several animals, you do no more than embrace the very man, those very men, for whom you are now preparing yourself in the art of love. Adoration cannot live without debasement, which is its twin. I must ask you to disrobe.”——

Whereupon Colère proceeds to have a sexual encounter with two dogs and a pig—mainly with the pig, a scene to which Hawkes devotes four pages. Apparently this is what Frederick Karl refers to when he describes Hawkes’s later novels as creating a “vision ... of breaking out, of movements beyond matrimonial convention, of developments in individual sensibility,” and what William Gass means when he speaks of the “glorious sensuality” of these books. There’s certainly nothing glorious going on here between people: men and women are forever abusing, abandoning, and betraying one another, the point apparently being that this is what intimate relationships are all about. They are founded not on love (there’s very little of that in these books) but on passion, which in Hawkes’s novels comes off as a form of totalitarianism.

Though Hawkes’s career breaks up neatly into two periods, certain qualities run through all the novels. There’s that prolix, pretentious style; that endless, amateurish pounding away at words like agony and desolation; that penchant for metaphors that sometimes don’t make much sense but must sound powerful to his ear (in The Blood Oranges, for example, the “distant fortress . . . cupped in the shriveled palm of desolation”); those endless series of rhetorical questions:

——Why then this decided sensation of erotic power? Why the implication of some secret design? What brilliant and, so to speak, ravaging guile could possibly be concealed inside that slender and merely partial form? Why did I smile immediately and Fiona cry out in happy recognition at the black hole driven so unaccountably into that small portion of the stone which, realistically, should have revealed no more than sexual silence?——

Most of the novels contain violence—murder, suicide. Hawkes remains clinically detached from his creations, but the obsessive cataloguing of chaos in the early books, and the exhaustive examination of sexual degradation in the later ones, makes it hard to overlook the possibility that this whole oeuvre is the product of a psyche desperate to dissipate its despair about mortality, entropy, and sin. This possibility, however, neither makes the early novels less tedious nor the later ones less offensive. The fan club seems to sense this, and has worked out explanations for all the gloom and grubbiness. Some suggest that Hawkes’s books are profound commentaries upon the near-psychotic extremities of human despair (in the early novels) and passion (in the later novels). Others-insist that his works are not meant to be taken seriously; they're supposed to be humorous, and if you don’t see that, you’re just obtuse. Hawkes seems to believe this himself. Witness the title of his new collection, Humors of Blood and Skin, and a few of his introductory remarks therein: “In The Cannibal I discovered an impulse toward comedy”; “The Beetle Leg is a mock . . . ‘Western’”; Travesty is “a comic novel.” Hawkesian humor is the subject of Greiner’s book, Comic Terror, in which he singles out for comtaient the scene in The Beetle Leg where Mulge’s mother Hattie dies and is buried above him in the dam: “Face down, eyes in dirt, she peered through the sandy side toward her son below, where he too lay, more awkward than she, feet up and head in the center of the earth.” Greiner’s gloss on this passage: “This kind of humor is not for everyone.” Humor? Hawkes’s comedy, you see, is “irreverent comedy at its best, designed not to amuse nor to provide a moment of quiet pleasure but to outrage,” to “counter .. . complacency.”

Countering complacency: that’s what it comes down to. The club’s favorite explanation for the gloom and grubbiness in Hawkes is, straightforwardly enough, that gloom and grubbiness are good for us. “One must confront the conceptual ugliness of human depravity,” says Kuehl, and no writer helps one to do so better than Hawkes, whose visionary fiction “communicates objectively and uncompromisingly the nightmarish aspects of irrational twentieth-century existence.” This notion of literature-as-emetic is common in academia, where the more nightmarish picture a novel paints of the contemporary world the more seriously it is likely to be taken; but the Hawkesians have carried the claims for the value of negativism to unprecedented lengths. Guerard, in his introduction to The Cannibal, set the fan club’s tone for all time when he wrote that “John Hawkes clearly belongs, perhaps this is to his credit, with the cold immoralists and pure creators who enter sympathetically into their characters, the saved and damned alike. Even the saved are absurd, when regarded with a sympathy so demonic: to understand everything is to ridicule everything.” What Guerard is doing here is singing the praises of a sensibility that sees very little distinction between virtue and evil, except perhaps for a tendency to be bored by the former and charmed by the latter. Does Guerard really consider immorality creditable and virtue absurd? Does Hawkes? Of course not—not in real life, anyway. But for the “demonic” Hawkes, and for the club members who have echoed Guerard’s praise through the years, moral values in life are one thing, those in literature another. It all just goes to show how little regard they have for a humanistic notion of the novel as a means of understanding life and how strongly they’re chained to an academic notion of the novel as a playing field for professors. Although it is hardly intended as such, Humors of Blood and Skin is the perfect testament to Hawkes’s lifelong indifference to the one conception, and his perpetual inability to break the ties that bind him to the other.

Humors of Blood and Skin: A John Hawkes Reader; New Directions, 320 pages, $22.50.

This article originally appeared in The New Criterion, Volume 3 November 1984, on page 70.

Copyright 2015 The New Criterion (www.newcriterion.com)

http://www.newcriterion.com/articles.cfm/John-Hawkes-s-fan-club-6803

Personal

| Owner | Roger D. Sarao, Jr. |

|---|---|

| Location | Library: Case 5, Shelf 5 |

| Purchased | May 04, 2012 for $ 28.80 at Apogee-Perigee, LLC, WA |

| Current Value | $ 75.00 |

| Condition | 1.5. Good Plus (G+)/Very Good Minus (VG-) |

| Quantity | 1 |

| Read | |

| Added Date | Feb 05, 2013 04:16:12 |

| Modified Date | Nov 16, 2016 16:00:12 |

Notes

05/04/12: Haven't bought a older, first edition book in some time. Just adding to my Hawkes collection. (RDS)

08/29/13: Per abe.com: "With autobiographical notes by the author and an introduction by William H. Gass. The hardbound edition (issued simultaneously with the softbound edition) consisted of only 750 copies, most of which went into library collections."

English

English  Nederlands

Nederlands  Deutsch

Deutsch  Français

Français  Español

Español  Magyar

Magyar  српски

српски  Dansk

Dansk  Svenska

Svenska  Slovenčina

Slovenčina  Português

Português  Movie Cloud

Movie Cloud Book Cloud

Book Cloud Music Cloud

Music Cloud Comic Cloud

Comic Cloud Game Cloud

Game Cloud